Designing Complex Boomerang Shapes: Complete Guide

Boomerang Theory of the Forms

Those who design their own boomerangs know how crucial the shape is to its flight. While classic shapes (Aboriginal, “A”, Napo, hook, etc.) are now well-known and mastered, the same cannot be said for boomerangs with complex shapes.

However, these are multiplying, which is interesting because they provide a double satisfaction: the beauty of the object itself (decoration) and its often original flight.

This article will help you design complex shapes that return perfectly. It is only a summary of Didier BONIN’s “theory of shapes.” The complete version is available in the book “L’essentiel du boomerang” (The Essence of Boomerang).

Table of Contents:

-

Boomerang Shape and Center of Gravity

-

Boomerang Basic Notions

-

Neutral and Non-Neutral Shapes

-

Role of Blade Profile

-

Keys to the Theory

Boomerang Shape and Center of Gravity

The most important characteristic of a boomerang (regarding its design) is its center of gravity (CG). How to find it easily? Here are 2 methods:

Method I

-

Tape your boomerang to a sheet of paper.

-

Suspend everything with a thumbtack or nail, letting it swing, with a plumb line attached to the nail. When balanced, draw a line on the sheet where the string is.

-

Repeat the operation, piercing the sheet with the nail in 2 other places.

-

The 3 lines must intersect at 1 point: this is the center of gravity.

Method II

-

Tape your boomerang to a sheet of paper.

-

Bring everything to the edge of a table to the limit of equilibrium. Then mark a fold on the sheet.

-

Orienting the sheet differently and repeating the operation, the intersection of the folds will give you the center of gravity.

Due to gyroscopic stability, the mass of the boomerang rotates around its CG. Thus, as soon as you transform the shape, you change the location of its CG and, consequently, the action of aerodynamic forces (ADF) in relation to this CG.

Boomerang Basic Notions

When a boomerang is thrown, it is given both a translational movement (with the arm) and a rotational movement (with the wrist). Thanks to the profiles, each blade will generate ADF throughout each rotation. It is in the high position that each blade will develop a maximum of ADF, because the speeds of translation and rotation are added, while they are subtracted in the low position (this is the principle of the advancing and retreating blades of helicopters).

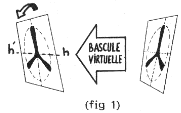

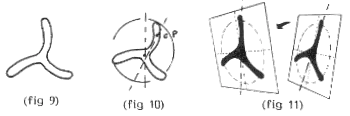

Over a complete rotation, all the ADF developed by the different blades will give a final resultant (sum of thrusts) which will always be located above the CG. The shift between the center of thrusts and the CG will create a moment of force “wanting” to tilt the plane of rotation of the boomerang around the horizontal axis hh’…

But the response to this “virtual” tilt will be caused by the effect of gyroscopic precession, 90° ahead of the plane of stress. In fact, the plane of rotation will pivot around the vertical axis vv’… and the boomerang will acquire a new orientation in space. (fig 1 and 2)

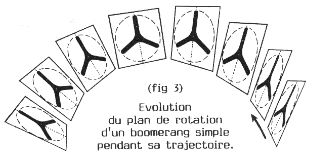

The sequence of these successive cycles will generate the overall trajectory of the boomerang. The boomerang reorients itself with each rotation and eventually describes a circle, returning to the thrower. (fig 3)

A classic boomerang is designed to be thrown with a near-vertical inclination. Attention! the term “near” is important: this slight inclination is intended to combat the inevitable weight of the boomerang!

In most cases, a classic boomerang will slowly lie down throughout its flight and thus regain height. But at the same time, losing energy, it slowly falls to the ground!

But it’s not always that simple, and we’ll see how the shape can influence the variation of the boomerang’s inclination during flight.

Neutral and Non-Neutral Shapes

With a conventional boomerang, the center of thrusts is located on the vertical axis of the plane of rotation: as long as the ADF act on this vertical axis, it will be said that the action of the shape of the blades is “neutral.”

A shape will be said to be “non-neutral” as soon as the center of thrusts is no longer located on the vertical axis taken into account until now. A blade may be sufficient, due to its shape, to shift the center of thrusts from this vertical, thus tilting the plane of the boomerang differently from a neutral boomerang, and causing a trajectory with an upward or downward tendency.

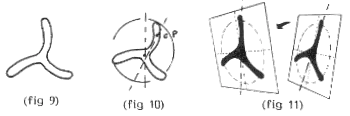

Take the example of a three-bladed boomerang whose plane shape of the blades is slightly curved forward. (fig 9) With this type of shape, the boomerang will maintain an inclination close to the vertical throughout the flight, thus obtaining a trajectory with a downward tendency, ideal for example for the speed event.

Indeed, the three blades will give their maximum ADF always above the CG but with a slight offset from the vertical of the plane of rotation (we will see later in which exact position the blades obtain their maximum ADF). The boomerang will then act in relation to a new vertical axis. (fig 10) We can see in figure 11 how the plane of the boomerang reorients itself with each rotation cycle:

This example illustrates the new speed boomerang design that appeared around 89-90 in competition. (fig 9) The three-bladed boomerangs were just beginning to be tolerated. With models made by Doug DUFRESNE, Chet SNOUFFER, or Eric DARNELL, leading throwers such as Grégory BISIAUX, Frido FROST, or lately Adam RUHF then smashed speed and endurance records.

A few degrees of variation in the curvature of the blades were enough to revolutionize this event!

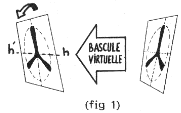

Conversely, if the blades are slightly curved in the other direction, the boomerang will have an upward trajectory. (fig 12 & 13)

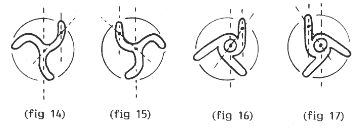

These effects can also be obtained with (three-bladed) boomerangs with off-center blades. (fig 14 to 17)

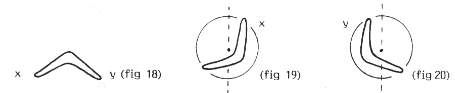

Let’s go back to the two-bladed shapes, which are not necessarily neutral. What happens with a classic shape called Australian (or Aboriginal) or banana? (fig 18) Surprise! We will see that this shape is not as neutral as it seems.

We will observe that the blades (x) and (y) will act differently from each other. When the blade (x) gives its maximum ADF, it will be behind the CG. (fig 19) This blade will therefore have a downward influence on the trajectory of the boomerang.

On the other hand, the blade (y) will give its full performance in front of the CG, having an upward influence on the trajectory. (fig 20)… Conclusion: if the 2 blades are equally profiled, the shape effects will compensate to give a normal trajectory in the end. But as soon as the blades have different profiles, the most effective one will be predominant and will generate an upward or downward effect.

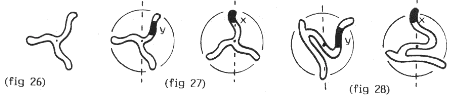

What happens with complex shapes? Take the case of the shape with originally curved blades. (fig 26)

In the case where the area (y) is strongly profiled and the area (x) is not, the blade will then act on the rear with a downward effect on the trajectory.

In the case where the area (x) is more profiled than the area (y), the blade will have its maximum ADF close to the vertical of the CG and therefore a more neutral effect. (fig 27) The same principle can be observed with the shape of the “Strange”: (fig 28)

You now understand that by acting on both the shape and the profile, the possibilities are numerous. Be aware that the more complex the shape of a boomerang, the more difficult it will be to develop and adjust. Also, it will often be more delicate to “place” it well in its trajectory at the time of launch. Thus, boomerangs with more complex shapes will often be more capricious.

Role of Blade Profile

We had until now provisionally isolated the “profile” factor to better observe the “shape” factor. We will now see what role profiling plays depending on its effectiveness. Let’s take as an example our downward-trending speed three-bladed boomerang.

1st case: if the boomerang is correctly profiled, we will indeed obtain a slightly downward trajectory caused by the starting shape. (fig 29)

2nd case: if the boomerang has narrower blades, the ADF may be stronger (but often of short duration!) and the boomerang may dive to the ground very quickly. (fig 30) We can say in this case that the boomerang is “too profiled”; it will then be necessary to reduce the thickness of this profile to obtain correct action.

3rd case: if the blades are weakly profiled (or if, for example, the boomerang has wider blades), the “diving” effect due to the shape will be partially or totally attenuated and the boomerang will regain a classic trajectory!

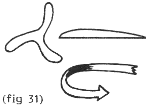

Here is a key point: the shape will only influence the flight if the profile is complicit. (fig 31)

Keys to the Theory

3 Factors for Maximum ADF (action of aerodynamic forces)

How to know in which precise position a blade will give its maximum ADF? Three factors will help you find this key position:

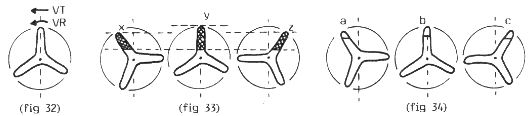

Factor #1: It is in the highest position of the circle of rotation that the speeds of translation and rotation will add up to reach a maximum total. For a neutral shape, the blade will then be on the vertical axis passing through the CG (fig 32)

In all other positions, the speed of rotation of the blade is no longer in the axis of translation and therefore loses its effectiveness in relation to the displacement, that is to say, in relation to the relative wind which generates the ADF.

Factor #2: It is also in this high position that the blade will present a maximum bearing surface to the displacement. In aviation, we would speak of “wing elongation”. Thus, in position (y), the blade will present a “maximum wingspan”, greater than that of position (x) or (z). (fig 33)

Factor #3: The last factor to consider is the width of the profile section in relation to the displacement. In the case of figure 34, there is no proof that in position (b), the profile section will have more performance than in (a) or (c) where it will then be a little wider.

This is in fact a false problem because if it were, for example, more efficient in position (a), it would also be in (c) and it is therefore the intermediate position (b) that will balance the forces.

Shape and Trajectory

Let’s now apply the previous 3 factors to the shape of our non-neutral speed type three-bladed boomerang. Observing figure 35: the problem will be to know if the blade will give more ADF in position (y) or (y’)?

We can guess that the position (y) will be predominant because the bearing surface is already maximum there and the speeds of rotation and translation are already acting in the same direction in relation to the displacement. The position (y’) will be almost as effective. It must be understood here that the blade will give its maximum performance even before choosing the vertical.

Even if the offset is slight, by adding, for one rotation, the combined action of the 3 blades, we understand that the sum of the thrusts will act on an axis offset from the vertical of the CG.

With the effect of gyroscopic precession, the plane of rotation will tilt differently from a neutral shape: the boomerang will remain rather vertical and thus obtain a trajectory with a downward tendency. Even a very slight offset will be enough to vary the trajectory.

Summary in Drawings

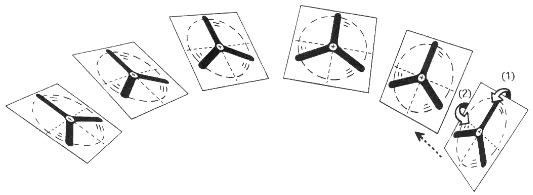

1st case: neutral shape

The virtual thrust (1) will generate, by the effect of gyroscopic precession, a real reaction in (2). The plane of the boomerang will therefore gradually lie down and the trajectory will be classic.

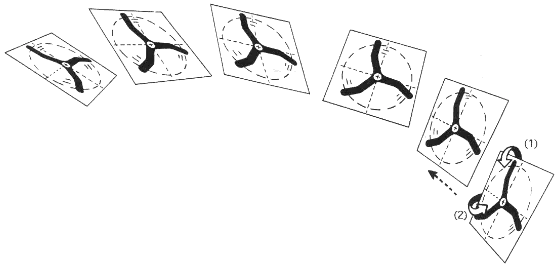

2nd case: blades curved backwards

The virtual thrust (1) offset towards the front of the axis of the CG will generate, by precession effect, the real reaction (2) also offset and accentuating the lying down of the plane of the boomerang. The trajectory obtained will then tend to be ascending.

Do not confuse this case where the trajectory remains curved with the case where the boomerang lacks profile, lies down and rises flat without a real return!

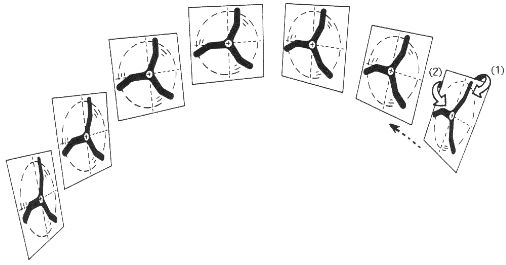

3rd case: blades curved forward

The virtual thrust (1) offset towards the rear will generate, by precession effect, a real reaction (2), also offset and acting in such a way as to delay the lying down of the boomerang, or even tilt the plane of the boomerang towards the interior. We will thus obtain a trajectory with a downward tendency (speed boom type).

A big thank you to Didier BONIN who authorized the publication of his study.

Keys to the Theory

3 Factors for Maximum ADF

How to know in which precise position a blade will give its maximum ADF? Three factors will help you find this key position:

Factor #1: It is in the highest position of the circle of rotation that the speeds of translation and rotation will add up to reach a maximum total. For a neutral shape, the blade will then be on the vertical axis passing through the CG (fig 32)

In all other positions, the speed of rotation of the blade is no longer in the axis of translation and therefore loses its effectiveness in relation to the displacement, that is to say, in relation to the relative wind which generates the ADF.

Factor #2: It is also in this high position that the blade will present a maximum bearing surface to the displacement. In aviation, we would speak of “wing elongation”. Thus, in position (y), the blade will present a “maximum wingspan”, greater than that of position (x) or (z). (fig 33)

Factor #3: The last factor to consider is the width of the profile section in relation to the displacement. In the case of figure 34, there is no proof that in position (b), the profile section will have more performance than in (a) or (c) where it will then be a little wider.

This is in fact a false problem because if it were, for example, more efficient in position (a), it would also be in (c) and it is therefore the intermediate position (b) that will balance the forces.

These guidelines should assist you in designing your ideal boomerang. Please note that patience is required and that progress is achieved through repeated experimentation. Finally, be aware that adjustments will vary based on the specific shape.